Historical Background

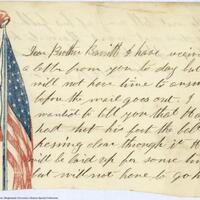

The War of 1812 is barely acknowledged in American social studies textbooks. It remains an obscure and little understood period of American history, falling between the traditional thematic divisions of the American Revolution and Jacksonian Democracy. For most people, the War of 1812 is simply recognized as the inspirational moment that gave America the Star Spangled Banner, as Francis Scott Key witnessed from a British ship the resolutely waving flag amidst the conflict at Fort McHenry in Baltimore; generated the dramatic narrative describing the legendary heroic feat of Dolly Madison, who rushed to gather up and save White House treasures just moments before the British burned down D.C.; and established Andrew Jackson as a military leader by his postwar victory (the Treaty of Ghent had already been signed, ending the war) at the Battle of New Orleans—a feat that subsequently earned him the Presidential election in 1829.

Aside from these iconic associations with the War of 1812, the global consensus is that the conflict was a minor hiccup in the greater ongoing struggle between Britain and France, its significance dwarfed by the almost simultaneous occurrence of the end of the Napoleonic Wars that brought about great changes in nineteenth century Europe. What are not as evident from the traditional historical interpretations of this time period are the great and lasting changes the War of 1812 brought about in the North American landscape. The nation of Canada was forged from the experience, and the many nations of Native people began to disappear from the North American map. While the Treaty of Ghent may have restored the European status quo antebellum, it forever transformed the North American landscape as the Treaty purposefully excluded Native Americans in the postwar settlement agreements, and the experience of the war left colonists in Canada with a new sense of unity and pride.

Both the British and the Americans had depended on Native American support in the conflict. Many Seneca, Onondaga, Oneida and Tuscarora of the Six Nations Confederacy fought with the Americans, while the Mohawk sided with the British. According to research done at the National Archives:

More than 1,000 Native Americans served during the War of 1812. They were organized in more than 100 companies, detachments, or parties. About half were Choctaws, and half were either Creeks or Cherokees. Units from other tribes included Blue's Detachment of Chickasaw Indians (discussed below), Capt. Wape Pilesey's Company of Mounted Shawano Indians, and Capt. Abner W. Hendrick's Detachment of Stockbridge Indians. (source: Collins, Prologue Magazine, Winter 2007, vol.39, no.4, paragraph 5)

Further west, along the Great Lakes border areas, the Indians under Tecumseh's leadership became allies with the British against the United States. The Potawatomi, Menominee, Ho-chunk, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Santee Dakota, Sauk, and Fox all fought as British allies in the War of 1812. Many of these First Nations had allied themselves early on with the French, but following British victory over the French in the War for Empire (French and Indian Wars), many of the Native communities now saw the British presence as the only wedge to keep the American settlers from advancing into their territories in the West and South. The Treaty of Ghent acknowledged not one concession to any Native American nation, even though several promises had been made during the conflict. Without British influence to preserve their land claims in negotiations, and with no formal or legal authority to recognize their role in the conflict, Native Americans were subsequently forced to endure a long and painful period from the end of the conflict up until at least the beginning of the 20th century, in which they would lose people, land, and dignity.

The alliances between Native Americans and the British in the War of 1812 increased hostile relations between some Native Americans and American citizens. This tension ultimately served to strengthen negative attitudes among American citizens, extending to more and more hostile government policies of the state and federal governments, often resulting in removal of Native people from their lands. Accounts of the deteriorating relations between Native people and Americans are numerous and can be found in records at local, state, and national repositories (see for example: Red Jacket Rejects Sale of Buffalo Creek Reservation: July 9, 1819, from SUNY Oswego's Granger Collection, andChronicles of Oklahoma, Indian Removal, from Oklahoma Historical Society).

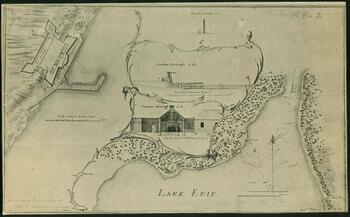

Following the American Revolution, the British loyalists who fled to what was then known as Upper Canada, had integrated themselves into British and French settlements that were now operating under British rule. When war broke out between the Americans and British, many colonists in Canada saw this as yet another affront to their British rulers. At the same time, American leaders and citizens were entertaining ideas of invading and taking Upper Canada from British control to counter the longstanding British foothold in Montreal and Quebec that allowed the British to continue to operate with force on the continent. The British strategy was to employ their superior naval strength to counter Americans along the eastern seaboard areas, specifically in the South (New Orleans), mid-Atlantic (Baltimore), and Hudson Valley (via the Great Lakes and Seaway), with the goal of driving a wedge between American forces in the North and South.

The British colonists of Canada, recognizing their precarious situation as a target for American forces hoping to cripple British naval superiority, rallied together to combat the invaders. To this day, Canadian history portrays with much patriotism the heroism of Colonel Brock and the Canadian forces at the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, much as American history recounts colonial forces overcoming great odds against the British army in the battles of the American Revolution. In the aftermath of the conflict, Canadian colonists struggled with the British government to gain more opportunities for self-governance, peaking with the 1837 Patriot War, resulting in the Unification of Canada in 1840 and, ultimately, independence for the nation in 1867.

War of 1812 in Western New York

In terms of local activity, the War of 1812 left an indelible mark on the physical, social, and political landscape. In her book, A History of the Town of Amherst, New York, 1818-1965 (*also found on New York Heritage here), former Town Clerk & Historian Sue Miller Young writes that during the War of 1812, American troops were stationed in Williamsville in the area between Garrison Road and Ellicott Creek. American soldiers and British prisoners were treated in a field hospital and log barracks that lined Garrison Road. A small cemetery, located on what is now Aero Drive, between Wehrle Drive and Youngs Road, was used to bury the men who did not survive their wounds or illnesses. General Winfield Scott used the Evans House (demolished ca. 1927) as his headquarters in the spring of 1813, when his entire army of over 5,000 men was stationed in Williamsville. Later the same year, when the British burned Buffalo, people fled to the safety of Williamsville and nearby Harris Hill.

Another local landmark is the site of the Flint Hill Encampment. The Army of the Frontier under General Alexander Smythe set up camp at Granger's farm during the winter of 1812-1813 in anticipation of invading Canada. Nearly 300 soldiers died there of camp disease. Farmers Daniel Chapin and Rowland Cotton were left to bury the dead in Granger's meadow, known today as Delaware Park (source: Historic Markers, Monuments, and Memorials of Buffalo, New York). For a long time after the conclusion of the War of 1812, American and British-Canadian relations remained strained and guarded. For this reason, the U.S. Army maintained a camp at Poinsett Barracks in Buffalo (now the location of the historic Wilcox Mansion on Delaware Avenue). The War of 1812 was and remains an important part of First Nations, Canadian, American, and local history.

Additional Resources

An American Time Capsule: Three Centuries of Broadsides and Other Printed Ephemera (Library of Congress)

British-American Diplomacy War of 1812 and Associated Documents (The Avalon Project, Yale Law School)

Early Canadiana Online

Free eBooks: War of 1812 (Digital Book Index)

Galafilm War of 1812

Guide to the War of 1812 (Library of Congress)

Native Americans in the Antebellum U.S. Military (National Archives)

Native Americans Mustered into the Service of the United States in the War of 1812 (USGenWeb Project)

Official War of 1812 Bicentennial Website

Re-living History: The War of 1812 (ThinkQuest)

Revolutionary War and War of 1812 Historic Preservation Study (National Park Service)

War of 1812: An Introduction

War of 1812 images from NYPL Digital Gallery (New York Public Library)

Local Resources

Biographical Sketch of the late Dr. Cyrenius Chapin (The Buffalo Medical Journal, vol.8, 1868-1869)

Buffalo History Museum Research Library

Buffalo Architecture and History, The History of Buffalo: A Chronology - 1812

Burning of Buffalo, N.Y.: December 30, 1813

Genesee County Military Notebook Collection (see War of 1812 notebook listings)

Historic Markers, Monuments, and Memorials of Buffalo, New York

Lewiston Public Library, Genealogy/History Room

Niagara Falls Chronicles of Our Early Settlers (see War of 1812 section)

Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812, by Benson J. Lossing (NY: Harper & Brothers, 1868)

Town of Cambria, Historian (see War of 1812 section)

War of 1812 Cemetery, Town of Cheektowaga, Erie County, New York